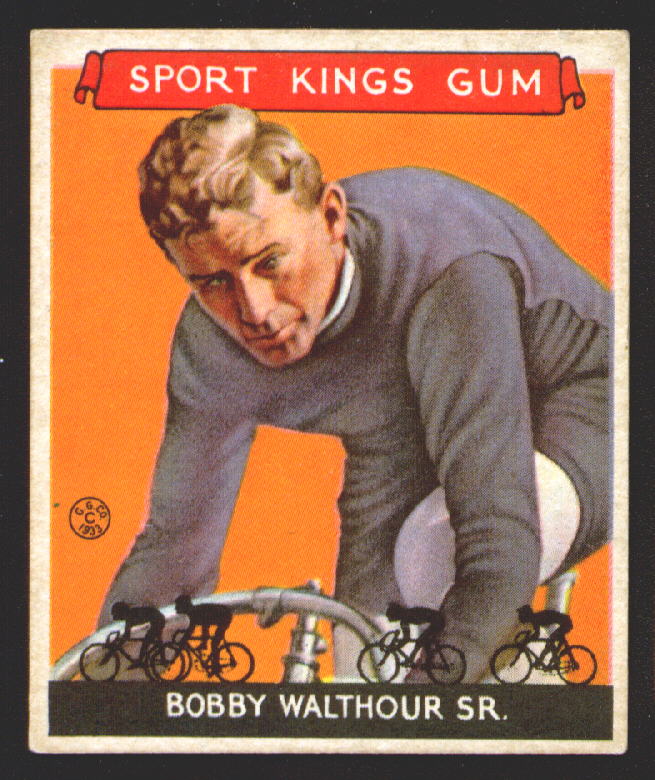

Thrills and Spills

Thrills and Spills

The Life and Times of

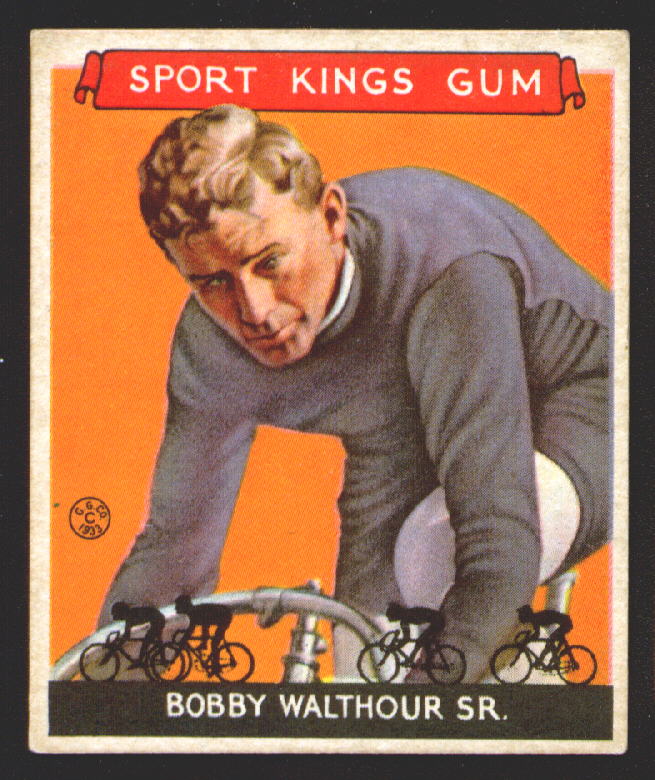

Bobby Walthour, Sr.

By Buck Peacock

Copyright 1999

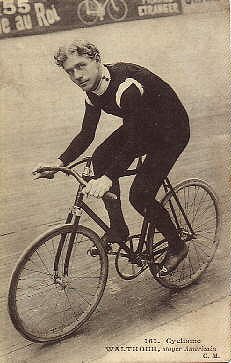

Mention the name Bobby Walthour, Sr. to the average non-bicyclist and all you get is a blank stare. Mention it to a hard core bicyclist and maybe you get "He was a racer, wasn't he? I think I read something about him somewhere.".

Until the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta brought the onetime hometown hero's name back into public view, the name of Bobby Walthour had not seen print in Atlanta since 1961 when the Atlanta Journal ran an article about the demise of bicycle racing. However, when he died back in 1949, the story was on the front page of both the Atlanta Journal and the Constitution and commanded almost a full column in the obituary section of the New York Times. It has been said by many that Atlanta focuses so much on its future, that it tends to steamroll over its past. In the case of Bobby Walthour, this could not be more true.

Bobby's life story was a true rags-to riches-to obscurity tale. He was born January 1, 1878 with twin brother Jimmy in the little town of Walthourville, named for his grandfather, near Savannah. There were six boys and one girl in the Walthour family. Somewhere around 1891, their mother died and the children were packed off to Atlanta to live with their Aunt Carrie. She took good care of them but they soon were out on their own. Older brother Palmer was working and moved in with a good friend, J. M. Selkirk, taking his brothers with him. The whole family showed an energetic and enterprising spirit early on. This would carry them far during a time when a man had to be tough and resilient to get ahead in the world. Bobby was working for Harry Silverman when he was fifteen and by the age of seventeen was a clerk at W. D. Alexander's bicycle shop and had his own place.

Bobby's career as a bicycle racer started out slow, but it seems as though there was never any doubt that that was to be his destiny. In late 1895 and early 1896 he had started to bloom. November 30, 1895 was set aside as Wheelman's Day at the Cotton States and International Exposition at Piedmont Park and Bobby and his good friend Will Johnson entered the festivities. Mr. R. L. Coleman, president of the Western Wheel Works in Chicago, makers of Crescent and other bicycles, organized the day-long affair, which included bringing down two trainloads of bicycle riders and journalists from New York and Chicago. The evening was spent at an elaborate banquet for 250 local wheelmen and out of town guests at the Kimball House, Atlanta's biggest and most elegant hotel. The event was sponsored in whole by Mr. Coleman on the occasion of his forty-fifth birthday in appreciation of the wheelmen of America who had contributed so much to his success. It was estimated that the day cost him approximately $20,000., a huge sum by today's standards and a fortune back then. In light of all the excitement created by the banquet, a huge bicycle parade to the Exposition grounds and the ongoing glamour of the Exposition itself, the races were almost lost in the shuffle. The oval around the Grand Plaza at the Exposition grounds in Piedmont Park was rolled and packed to create a fast racing surface, but it was really not very fast at all. In the professional half mile and one mile events, P. J. Berlo of Chicago won, paced by the celebrated Humber team quadruplex, a four man pacing bicycle. Bobby entered the class A, or amateur, races and won the one-fourth mile race and finished second to Lum of Birmingham in the half mile and second to Dudley of Americus in the one mile State Championship. Not a bad showing but then again, this was just a boy on the way up.

Bobby really showed what he was made of the next spring. In the Pigott ten mile road race, Bobby started at scratch and Will Johnson started a minute earlier. These were positions assigned to them by a handicapper (a man familiar with the abilities of the racers), in order to have everyone finish at approximately the same time. Johnson crossed the line first, winning the race, but Bobby was not far back. He captured the time prize by two seconds from Cleveland Bolles, an older and more experienced racer, in a hot sprint finish. He was the fastest man of the day.

This was only a prelude, however, to the real Bobby Walthour. In May, a state League of American Wheelmen meet was scheduled to be held at Columbus. Tired of being an also ran, Bobby got his revenge in a big way. He had been under the tutelage of Gus Castle and Gus had him prepared. Among other training routines, he was to ride down Peachtree Street at the hill leading to Peachtree Creek as fast as he could. This is the now famous "Heartbreak Hill" from the Peachtree Road Race. Anyone who has ridden a fixed gear bicycle down a steep hill knows how difficult this is. Try doing it on an unpaved road! This developed tremendous leg speed and an explosive sprint for Bobby. At Columbus he won every race that he entered. One, the state championship, was declared no race because of a protest by another rider. The Columbus newspaper labeled him "Greedy Walthour". In the process, he easily dusted Johnson, Lum, John Chapman and Dudley, the reining state champion. Bobby emerged from this meet as the champion of the south and the de-facto state champion. He was eighteen years old and had beaten all the top riders in a most convincing fashion. This was a major turning point in his career. After this, he considered himself a professional bicycle racer.

One week later, on May 14, Bobby had another experience that was to foreshadow his lifelong experience in bicycle racing. While riding to a friends house at a rapid clip, the fork on his bicycle broke and he was hurled to the ground. He was knocked unconscious, but otherwise only bruised and he soon recovered. Later throughout his career he sustained numerous broken bones, cuts and loss of skin from falls on the track. Many of these were at speeds of forty or fifty miles an hour. The tally goes something like this: right collar bone, 29 times; left collar bone, 15 times; ribs, 32 times; fingers, 6; thumb, 1; arms and other bones, too many to count. Twice after accidents, he was at first assumed dead. The sport was a rough and tumble business, not for the faint of heart. Many times Bobby even raced with broken bones mending. He could get up after being knocked out for an hour and finish a race.

During the summer of 1896, Bobby traveled around the South racing. He raced in Montgomery, Birmingham and Savannah and in late July took a ride with his close friend John Chapman from Atlanta to Nashville, Tennessee. This is an indicator of the level of fitness that these riders had back then. There were few paved roads anywhere and a mountain crossing on a single speed bicycle would have been quite a feat. Nevertheless, it was all in a day's work for them. In Montgomery, Bobby won his first races as a pro. At Nashville he rode on his first indoor board track, winning against such riders as Bert Repine and Jay Eaton, known then as the "King of the Indoor Tracks". From Nashville he went to Louisville in August for the League of American Wheelmen National meet and did well there. Bobby must have taken up residence in Nashville for a while, for at the next race that he entered in Atlanta, he was listed as being from there. This race was held October 8 at Piedmont Park, and was a great success. Bobby lowered the state record for the half mile paced by a tandem. His time of one minute, four seconds knocked one second off the previous record set by world champion John S. Johnson in 1894.

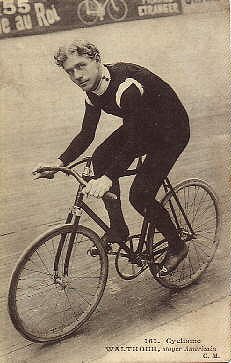

The next year, 1897, profiled in the previous installment, propelled Bobby into national prominence. The Coliseum, the velodrome at Piedmont Park, opened and Bobby was Atlanta's home team, so to speak. He tried to race there as often as he could, but the National Circuit took him to New York, Philadelphia, Boston and other northern cities that this true southern boy had heretofore only heard of. It was baptism by fire, but Bobby did fairly well, placing in some of the professional handicap races.

Much of the cycling activity in Atlanta that year centered around society. In April, the Piedmont Cycle Path was opened for members of the Piedmont Cycle Club. This club had been organized November 16, 1896 and was the cycling equivalent of the prestigious Piedmont Driving Club. Membership was $10.00 and only members were allowed on the path. The cyclists entered the path near where Rhodes Hall sits on Peachtree Street and wound its way north through the woods on the west side of Peachtree, exiting near the intersection of Collier Road with Peachtree. Judging from descriptions in the newspaper at the time, it was an area of beauty only slightly exceeded by the Garden of Eden.

In 1898 the Coliseum was going full bore, but without the continued presence of Bobby Walthour, the racing was lackluster. He made several swings down south, but it was clear by now that he was destined to ride up north, where the big money races were. He was making a reputation for himself and Atlanta both, for people in those days tended to equate a successful man with his roots.

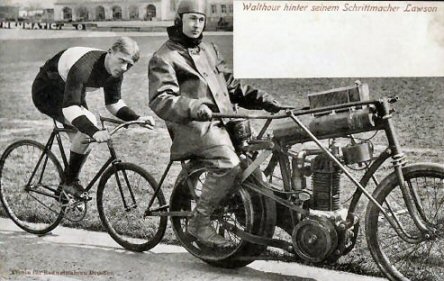

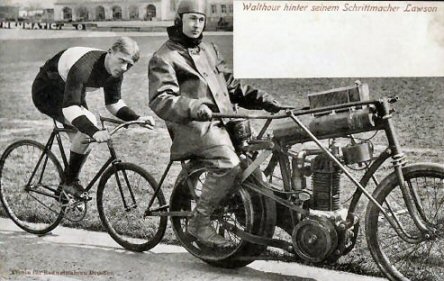

In 1899, Bobby entered another critical phase of his professional career. He was introduced to the motorcycle. Most racing then was behind pacing machines, with anywhere from two to five riders pedaling, and Bobby had established himself as an exceptionally good stayer, as the racer following was called. The advent of the motorcycle made it much easier to attain the speeds which are possible when tucked in behind a draft. Motor-paced racing began in England in 1895 and Bobby discovered it up north, to where it had naturally migrated. He brought it down south with him in the fall when he returned for one of his visits to race before the home crowd. He purchased a motor tandem from the Orient Cycle Company in Waltham, Mass. to use in the races. It was a huge machine weighing nearly 300 pounds and geared to 170 inches. With each turn of the cranks it would travel half a block. It was the first motorized machine in the state of Georgia. The purpose of being a tandem was so that one man could steer while the other would operate the motor. To say that it created wild enthusiasm is an understatement. It was a mind boggling thing to the people of 1899. It was as loud as a locomotive and ran at a speed difficult to comprehend for them. The three machines used in the races had nicknames which give a good idea of what people thought about them: the "Infernal Machine", the "Go Devil", and the "Devil Catcher". The races were originally scheduled to be held on the dirt track at Piedmont Park, but because of heavy rain they were moved indoors to the Coliseum. The sight of two motorcycles followed by bicycle riders whirling around a sixth of a mile indoor board track in excess of thirty miles an hour must have been stunning. Add to this the deafening noise and you get quite a picture. Bobby rode against Jay Eaton, the "Indoor King", but lost in a closely fought race. All in all, it was an exciting weekend and an important historical interlude in the life of the city of Atlanta.

In motor-paced racing, Bobby had found the perfect outlet for his abilities. In 1902 and 1903 he was professional national champion and in 1904 and 1905 he was world professional champion. He took second in the 1910 worlds. He won the fabled New York six-day race in 1901 with Archie McEachern and in 1903 with Bennie Munroe. He raced well into the 1920's, much of it in Germany, France and Belgium, winning races when he was in his forties. Bicycle racing historian and author Peter Nye rates him one of the three greatest American racers of all time. The stories behind these accomplishments are fascinating.

He is in the New York Sports Hall of Fame, the U. S. Bicycling Hall of Fame in New Jersey and the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame, but unfortunately his hometown has all but forgotten him. The area is replete with highways, streets, parks and buildings named for anybody who knew somebody, but the Walthour name is conspicuously absent from the Atlanta landscape. Bobby was a true Georgian and an ambassador for Atlanta wherever he traveled throughout the world. He was a fine and moral man, refusing to race on Sundays. He worked for the YMCA during World War I when he was too old to serve his country in battle. For many years, the only athletes to achieve greatness from Georgia were Ty Cobb, Bobby Jones and Bobby Walthour. And for many years, everyone in Atlanta knew when you talked about "Bobby", it was Walthour not Jones. He still ranks near the top of Georgia born athletes for his accomplishments.